Ocean Bottle: Supporting blue carbon beyond offsetting

This blog was written in collaboration with Ocean Bottle, who have supported ACES’ projects for several years as part of their commitment to improving the health of the ocean and our planet. This blog was written as part of our ‘financing blue carbon ethically, responsibly and effectively’ series and explores different approaches to compensating for corporate carbon footprints and supporting marine conservation.

Ocean Bottle have supported ACES’ mangrove and seagrass projects for several years as part of their commitment to making the ocean, and our world, a better place. Ocean Bottle’s approach to sustainability goes beyond carbon calculations and ‘net zero’; that equating carbon emissions to offset purchases is inadequate. In line with this ethos, they are moving beyond carbon offsetting to a holistic approach to carbon reductions and developing carbon sinks by protecting natural ecosystems such as mangrove forests and seagrass meadows. This blog, written in collaboration with Ocean Bottle, explains the reasoning behind their strategy for emissions reductions and compensating for their unavoidable emissions. Ocean Bottle’s reasons for moving away from offsets include ethical, political and technical challenges to offsetting as a concept and the current offsetting landscape; this reasoning is described well in this document. Here, we focus on the political ethics of carbon offsetting, which raises important questions regarding how the offsetting landscape can be improved in order to incentivise systemic change.

The perspectives presented here are Ocean Bottle’s; however, as ACES, we welcome debate around carbon offsetting and support Ocean Bottle in their emissions reduction strategy. We are pleased to be able to continue working with Ocean Bottle on the development of blue carbon conservation and restoration activities in a way that goes beyond carbon credits.

Emissions reduction strategy

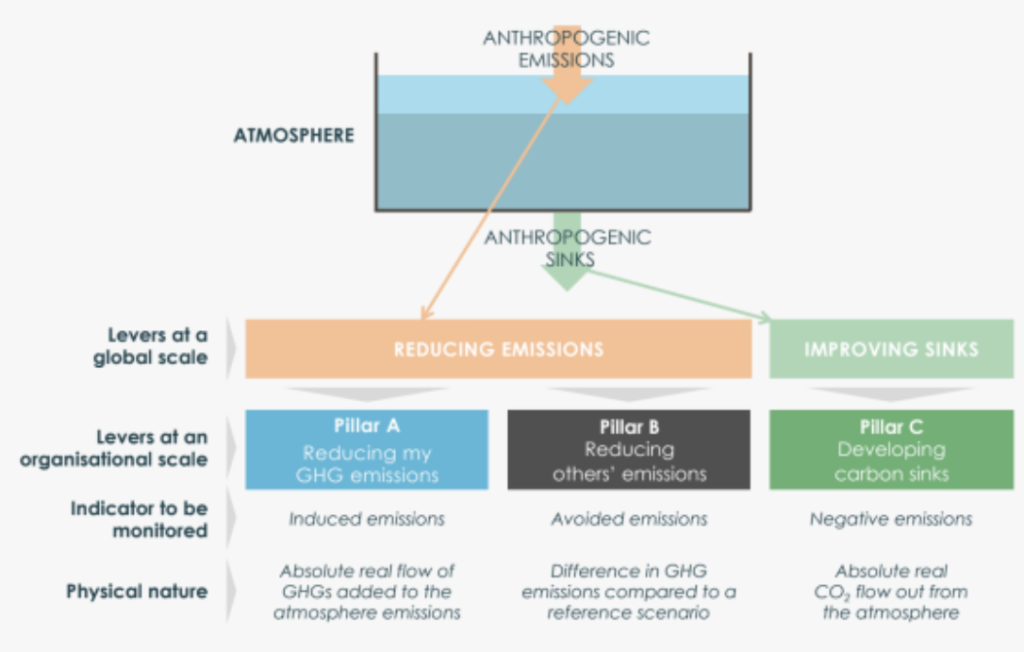

Ocean Bottle’s Emissions Reductions strategy follows three pillars: first by implementing emission reductions through their supply chain, then avoiding emissions in their value chain, and when necessary, developing carbon sinks by protecting natural ecosystems outside of their value chain. This follows the Carbone 4 emissions reductions framework.

While this framework is broadly similar to the ideal scenario for offsetting – reducing your scope 1 & 2 emissions, then scope 3 emissions, followed by offsetting or insetting unavoidable emissions – the biggest differences lie in pillar C.

Firstly, under Carbone 4’s framework, unavoidable (or residual) emissions should be compensated for through the development of carbon sinks such as blue carbon ecosystems. This is similar to ‘removal credits’ – carbon credits that result from the removal of CO2 from the atmosphere – but does not allow an equivalent to ‘reduction credits’ – credits which result from the reduction of CO2 entering the atmosphere. (It is important to note here that removal credits are also sometimes valued and preferred over reduction credits – such as in the Oxford Offsetting Principles).

Secondly, Carbone 4’s framework does not specify that offsets should be used to compensate for unavoidable emissions; it allows for a broader approach to funding activities that enhance natural carbon sinks. This is where Ocean Bottle’s perspective has changed from buying carbon offsets to a more holistic approach to enhancing blue carbon sinks.

Choosing carbon sinks over offsets

If Ocean Bottle are committed to funding the development of carbon sinks like mangroves and seagrass, why are they moving away from offsetting?

Offsetting as a concept has been heavily scrutinised, and the debate around the politics and ethics of offsetting has divided opinion. Critics of offsetting question whether offsetting allows society to delay making systemic changes – i.e., actual carbon reductions – by simply paying for offsets to compensate for carbon emissions. Whilst the morally responsible approach should be to first reduce your direct and indirect emissions as far as possible – as outlined in Carbone 4’s framework – there is nothing to mandate companies to do so (or indeed, to reduce or offset their emissions at all). Likewise, there is no regulation of how companies present or communicate their carbon reductions – a company that offsets all of their emissions without making reductions can report the same emissions reduction targets as a company that has made genuine carbon reductions in their own activities and supply chains (and has therefore contributed to systemic change). Actors in the offsetting market, including ACES, can and do take voluntary steps to guard against this injustice; however, Ocean Bottle’s perspective is that they do not want to play a part in a system that permits less ethical companies to take advantage of unregulated emissions reductions and reporting.

“The reporting and carbon reduction strategy enforcements vary from country to country, but are, for the most part, only voluntary. This means that sub-par efforts and greenwashing by the world’s largest emitters will largely go unpunished.”

– Ocean Bottle

This raises an important question: what can be done to hold companies to account on their emissions reductions and offsetting (or other mitigation actions)? How can companies with genuine commitments to actually reducing their emissions, offsetting only their unavoidable emissions and if they do need to offset, researching their options and choosing high-quality credits with evidenced co-benefits – from companies that simply ‘pay to pollute’ by offsetting without reducing? There needs to be a clear, internationally-aligned reporting system under which consumers can scrutinise the steps that companies are taking to lower their carbon footprints, and thereby hold these companies to account. This would be a significant step towards facilitating systemic change – publicly rewarding companies like Ocean Bottle that go above and beyond to not only compensate for their emissions but have a positive impact through supporting projects that deliver biodiversity and community benefits.

Net zero: a global concept

By definition, a company cannot be carbon neutral… A better terminology which companies and individuals should follow, is to contribute to global neutrality with the purchase of offsets and other mechanisms.”

– Ocean Bottle

When the concept of ‘net zero’ was popularised in the conception of the Paris Agreement, it referred to global emissions – achieving an overall balance of sources and sinks of global greenhouse gases. It is only more recently that the term ‘net zero’ has been used by companies as a label of their emissions reductions or offsetting. Ocean Bottle, among others, believe that the concepts of net zero or carbon neutrality cannot be claimed by individual companies unless they are actively sinking carbon from the atmosphere – if they are still producing emissions then they are still a carbon ‘source’, regardless of offsets. Ocean Bottle suggest that rather than making ‘net zero’ or ‘carbon neutral’ claims, companies should use terminology such as “contributing to global neutrality with the purchase of offsets and other mechanisms”. They believe that not being able to trumpet about self-proclaimed neutrality will deter most companies from relying on offsets.

ACES perspective

Ocean Bottle’s approach to their emissions reductions is a gold-standard example of how companies can meaningfully engage with the climate crisis and their role in fighting it. They have critically questioned their own activities, including their emissions reduction activities so far, and shaped their way forwards based on extensive research and evidence-based perspectives.

Whilst their full reasoning for minimising their use of offsets is not always fully aligned with ACES’ views, we welcome debate regarding the ethics, politics, effectiveness and social justice of offsetting and our partnership with Ocean Bottle allows us to present this diversity of views on an open platform. Ultimately, we and Ocean Bottle share the same end goal: to contribute to a landscape in which climate action by companies is transparent, genuine, effective and socially and environmentally just.